In the book, The Wisdom of Teams, Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith define a team as “a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.” There are some valuable aspects of this definition that are worth discussing. First, note that teams are described here as generally “small.” Keeping a team small (12 or fewer members) allows team members to develop better relationships and communicate more directly.

Second, team members have “complementary skills.” While individual team members may not possess all the skills required to complete a project on their own, the team collectively has the necessary skills. This could mean the team consists of specialists who all own their roles in the project, but agile methods also promote the use of generalizing specialists (multi-skilled individuals who can readily move between roles). Generalizing specialists with cross-functional skills can perform many different tasks on projects and can help smooth resourcing peaks and troughs.

Third, teams are defined as being “committed to a common purpose.” This means team members are aligned with a project goal that supersedes their personal agendas. Teams also share common “performance goals” and a common “approach.” In other words, team members are in alignment (if not always in agreement) as to how the goals will be measured and how the team should go about the work. Finally, there’s the idea that team members “hold themselves mutually accountable.” In other words, the team has shared ownership of the outcome of the project.

Many people have researched how we build high-performing teams, including Carl Larson and Frank LaFasto, authors of the book Teamwork. Larson and LaFasto interviewed a wide range of teams, including the space shuttle Challenger investigation team and executive management teams, and discovered a surprising consistency in the characteristics of effective teams. In their book, the authors explored the eight properties of successful teams and examined priorities in building a high-performance team. The following guidelines are influenced by their research:

- Create a shared vision for the team: Doing so enables the team to make faster decisions and builds trust.

- Set realistic goals: We should set people up to succeed, not fail, so goals need to be achievable.

- Limit team size to 12 or fewer members: Small teams communicate better and can support tacit (unwritten) knowledge.

- Build a sense of team identity: Having a team identity helps increase each team member’s loyalty to the team and their support for other team members.

- Provide strong leadership: Leaders should be there to point out the way, and then let the team own the mission.

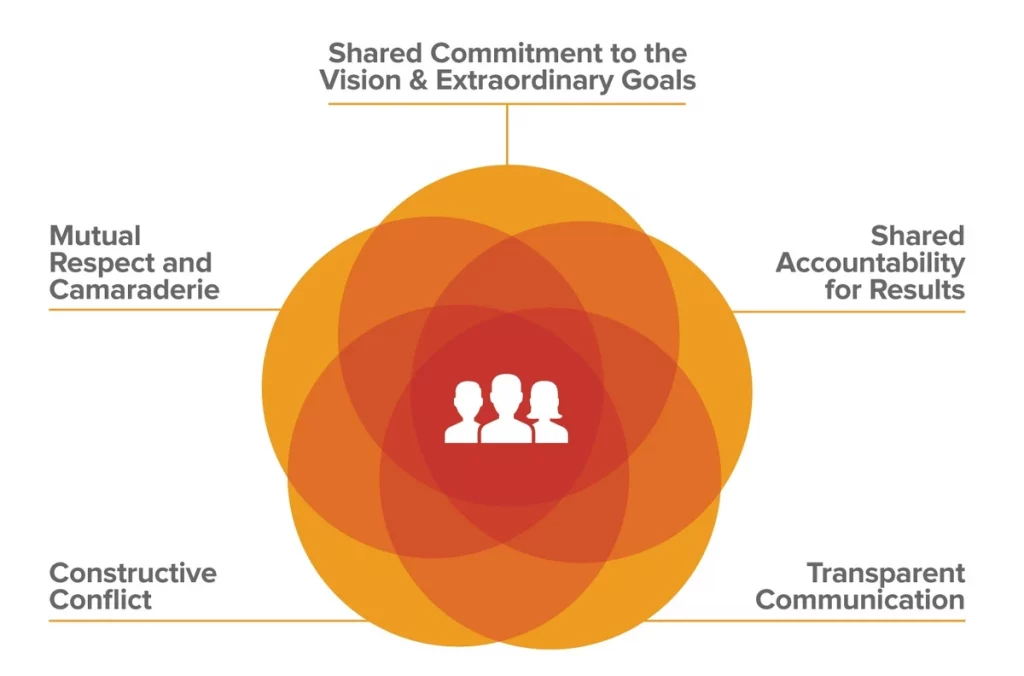

Lyssa Adkins, an author of Coaching Agile Teams, has also explored the concept of a high-performance team and identified the following characteristics of such teams:

- They are self-organizing, rather than role- or title-based.

- They are empowered to make decisions.

- They truly believe that as a team they can solve any problem.

- They are committed to team success vs. success at any cost.

- The team owns its decisions and commitments.

- Trust, vs. fear or anger, motivates them.

- They are consensus-driven, with full divergence and then convergence.

- And they live in a world of constant constructive disagreement.

Let’s look at these characteristics in more detail. Members of self-organizing, empowered teams are freed from command-and-control management and can use their own knowledge to determine how best to do their job. Empowering teams enables organizations to tap into people’s natural ability to manage complexity. We manage complexity every day, by juggling our work life, home life, e-mails, phone calls, and appointments. Organizations often fail to capitalize on this ability when it comes to executing project tasks, however. Instead of presenting team members with a number of items that have to be accomplished, they present a set of ordered tasks that, in reality, might best be done in a different way. Allowing teams to self-organize enables us to use the individual complexity management skills that we all have.

The recognition that the team is in the best position to organize the project work is liberating and motivating for the team members. People work harder and take more pride in their work when they are recognized as experts in their domain. When self-organizing teams select work items from the queue of waiting work, they have the expertise to choose those items that are not blocked for any reason, that they are capable of doing, and that will bring them toward the iteration goal. This practice alleviates many of the technical blockages seen in push systems where the task list and sequence are imposed on the team.

Thus we need to delegate responsibility for success to the team and allow them to do what is necessary to achieve the goal. This is the “downward serving” or servant leadership model used by agile methods. Instead of a “directing” style, which is a command-and-control approach where instructions are passed from the project manager to team leads down to team members, agile projects take a servant leadership approach, where the project manager or leader shields the team from interruptions, removes impediments, communicates the project vision, and provides support and encouragement.

Using trust (rather than fear or anger) as a driving force in teams’ motivation helps the team in establishing open, honest, and transparent communications. Trust is a key factor in team building and a needed enabler for cooperation. A high-performance team increases trust by building a culture of partnership and shared values. In general, trust-building is a slow process, but it can be accelerated with open interaction and good communication skills. Trust building needs personal knowledge and regular face-to-face interaction, but it also requires empathy, respect, and genuine listening.

Trust along with item 7 (“They are consensus-driven, with full divergence and then convergence”) speaks to establishing a safe environment in which team members debating or arguing over issues is seen as healthy and is encouraged because this practice ultimately leads to better decisions and stronger buy-in to those decisions once they are made. Divergence (the argument and debate) and convergence (the agreement about the solution) increase the team’s commitment.

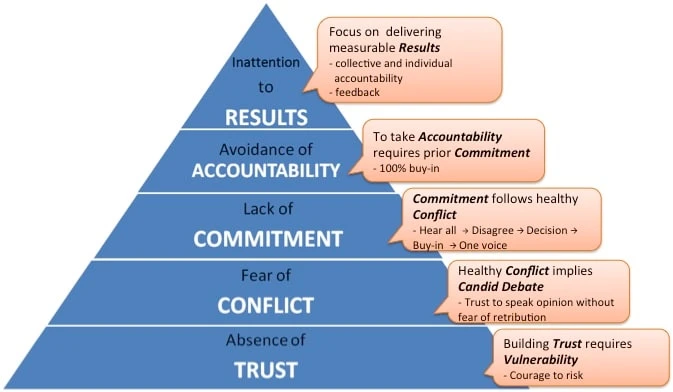

Item 8 (“High-performance team live in a world of constant constructive disagreement) is related to item 7. Constructive disagreement is vital to really understanding and working out issues. Patric Lencioni, the author of The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, lists the following dysfunctions that damage and limit team performance:

- The absence of trust: Team members are unwilling to be vulnerable within the group.

- Fear of conflict: The team seeks artificial harmony over constructive, passionate debate.

- Lack of commitment: Team members don’t commit to group decisions or simply feign agreement with them.

- Avoidance of accountability: Team members duck the responsibility of calling peers on counterproductive behavior or low standards.

- Inattention to results: Team members prioritize their individual needs, such as personal success, status, or ego, before team success.

These dysfunctions all stem from avoiding conflict (or constructive disagreement) and not having a safe environment where it is okay to ask questions. Establishing a safe environment for disagreement is key to success; such an environment allows team members to build a strong commitment to decisions. If they have such a commitment when they encounter the inevitable obstacles on a project, rather than returning to management with a list of reasons why something cannot be done, they instead push past the obstacles or find a way around them.

In conclusion, a high-performance team is a small group of people with complementary skills that are united by a common purpose, performance goals, and approach. To be successful, teams should have shared vision, realistic goals, team identity, strong leadership, self-organization, empowerment, belief in their ability to solve problems, commitment to team success, ownership of decisions and commitments, trust, and consensus-driven decision-making with constructive disagreement. These characteristics enable teams to be agile, adaptable, and responsive to change and are essential for achieving high performance.